It is widely known that women have less access than men to agricultural extension services. Extension agents most often speak to household heads who tend to be men, as well as other male farmers. Plus, the extension agents themselves also tend to be men. Women often work longer hours than men too (12-17 hours per day compared 8-10 hours for men) which includes childcare and responsibilities in the house, leaving them little time to access extension advice.

In a paper published earlier this year, CABI’s Frances Williams and co-author Avinandan Taron assessed women’s access to extension services through Plantwise as a baseline for future comparisons of women’s access through other extension approaches. The research, published in The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, also looks at whether men and women farmers seek plant health advice on the same crops in order to disperse continuing assumptions made about which crops women and men grow.

There are a number of different extension approaches used around the world, from farmer-to-farmer extension, to farmer field schools. However, there is little to no quantifiable data on women’s access to extension. This lack of data has meant that understanding the most effective approaches to increasing women’s access are unknown; making it impossible to target efforts towards these approaches.

By analysing data from 13 different countries in the Plantwise Online Management System (POMS), the authors found that the Plantwise extension approach enables higher levels of women’s access than generally reported for extension and that the crops that farmers seek advice on is not gender dependent.

One of the barriers to women’s access to extension services could be down to the preconceptions that women only grow subsistence crops and are not involved in growing cash crops because of their roles in ensuring household nutrition. Perhaps the lack of data about crops grown by women has contributed to the idea of men’s crops and women’s crops.

Through the Plantwise approach, which is demand-led, all farmers are welcome to attend plant clinics which are established in public areas. The clinics are free and farmers can bring along a sample of their crop, which is then diagnosed by a trained plant doctor who can offer advice on how best to manage the plant pest and/or disease attacking the crop. Their recommendation is written up as a prescription for the farmer and includes data on farmer location, gender, crop brought, diagnosis and recommendation, all of which is also entered into POMS.

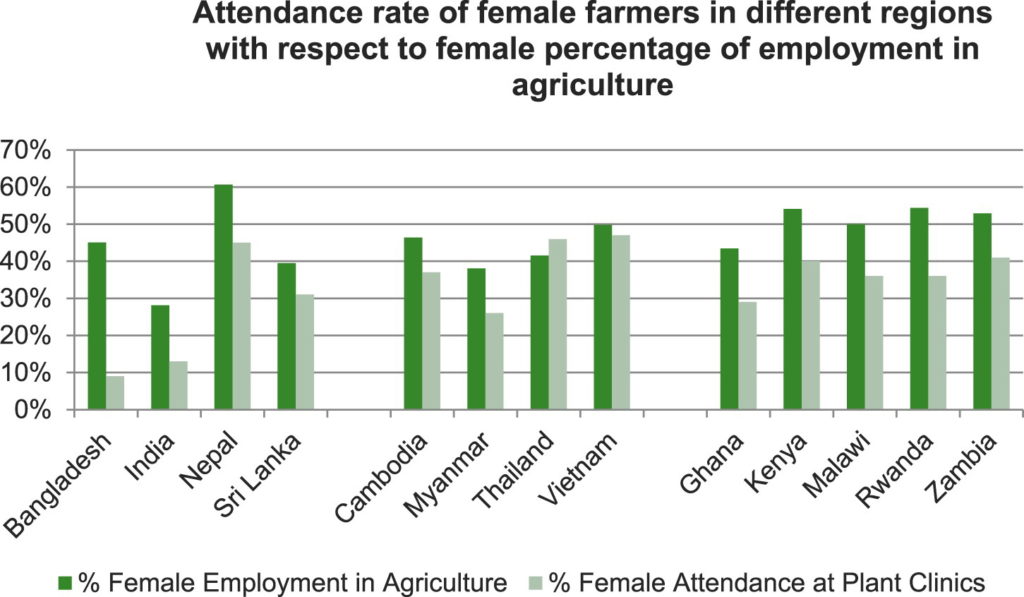

Using this data, the authors found that when it came to attendance patterns at plant clinics, South East Asia recorded the highest proportion of women’s attendance, followed by sub-Saharan Africa and then South Asia with the lowest. The authors compared this to national statistics on women employed in agriculture.

This analysis showed that the country with the lowest access by women was Bangladesh. This could be explained by country cultures such as those which restrict women’s movement outside their homes as well as their interactions with men who are not family members. In contrast, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam showed a low gap between employment in agriculture and attendance at clinics, which could reflect the more equal role of women play in agriculture in South East Asia.

Over time, attendance at plant clinics stabilizes for both men and women farmers once attendance has reached a threshold of visitors per year. In Sri Lanka and Kenya for example, once the clinics get over 1,000 visitors per year, an increase in male visits is matched by an increase of women farmers and vice-versa.

By analysing the crops brought to plant clinics, the authors found that “both women and men are likely to demand extension advice on the same crops.” The paper aimed to explore the ‘male vs female’ crop narrative so commonly found in agriculture and the results show that it does not appear to hold up in the countries examined, aside from Bangladesh where gender disparities remain stark.

“This shows that assumptions shouldn’t be made about women’s and men’s roles in agriculture, based on crops,” said lead author Frances Williams. “In many cases, it is a joint decision in the household about which crop to grow.”

Although the authors stipulate that more research is needed, their paper does show that demand-led extension like the Plantwise method can increase access not only for women farmers, but all farmers.

Read the article in full with open access: Frances E. Williams & Avinandan Taron (2020) Demand-led extension: a gender analysis of attendance and key crops, The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, DOI: 10.1080/1389224X.2020.1726778

Learn more about our work in gender:

Gender Assessment of Plantwise Programme

Empowering female farmers – Gender responsive programming

Related News & Blogs

Empowering women farmers through Gender Technical Working Groups

How PlantwisePlus is championing gender equality in agriculture through GTWGs Gender Technical Working Groups play a vital role in advancing equality in rural communities. Women in villages often have less access to knowledge, resources and power…

23 May 2025