In the search for new bioresources in increasingly remote and rural regions, researchers will use the traditional knowledge of local communities to support their search for new, untapped plants, animals or chemical compounds. The ethical (and sometimes political) issues surrounding this come when this knowledge is used without permission, and exploits the local community’s assistance and culture for commercial gain. This is called biopiracy.

Biopiracy occurs when research organisations take resources without official sanction, most often within marginalized people and less affluent countries. Biopiracy is not only limited to drug development – where the majority of media attention comes from – it has also been found to occur in agricultural and industrial contexts, such as with certain biocontrol chemical products. A number of Indian plant-derived products from the neem tree (Azadirachta indica), turmeric, and Darjeeling tea have all been patented by foreign firms for lucrative purposes.

The act of searching for biological or chemical resources for commercialization is known as bioprospecting. Ideally, this would involve increased ethical consideration during the entire biological or chemical resourcing process, including content, accessibility, benefit sharing, and legal agreements between groups before the research even begins. Complete bioprospecting includes the return of earnings and profits towards local communities, conservation efforts, and the development of infrastructures to benefit the local population.

Biopiracy may occur within a single country, but, it is more commonly seen with organisations taking advantage of low- and middle-income countries, regions or communities. This only serves to accentuate power inequalities between more developed, financially stable countries and less economically and technologically developed countries. It also has roots in colonialism, with former colonies having many of their internationally sought-after resources taken without consent or under fair, legal agreements. Examples of this include pepper, sugar, coffee, and rubber; all of which are major products on the international market and have their origins in colonialism.

At the core of biopiracy is the concept ownership of resources. For many indigenous groups and rural communities, the idea of trademarks and patents for living organisms and resources is illogical, as well as the concept of having specific individuals assigned as the owner of an entire resource. To fuel the contradicting beliefs and understandings, the laws related to intellectual properties, trade and biological conservation can vary between countries, with specific details regarding patents (i.e. what can be patented, for how long, etc.) differing between legal frameworks.

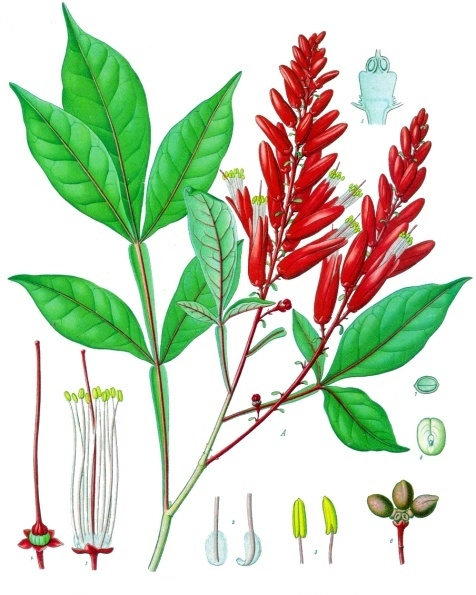

A good example of a biopiracy case occurred in 2005, between the French Institute for Development Research (IRD) and local officials in French Guiana. Researchers were carrying out interviews in French Guiana to discover local knowledge of botanical antimalarials. The findings from these interviews were later published in 2009, which was then used to acquire a patent for a new biological compound from the plant Quassia amara for its antimalarial properties.

This started a biopiracy and ethical debate, in which the IRD claimed to have found this compound via alcohol-based extraction methods of the plant, not from the traditional tea preparation methods used in the local communities. This was the IRD’s basis for their claim to the rights for the antimalarial; it did not come from traditional Guianese methods, but from scientific research. But what about the local knowledge about which plants to investigate in the first place which helped the researchers avoid wasting time studying thousands of other potential plants? According to recently implemented laws, official agreements should have been made between the IRD and French Guiana before the research began. The two sides are still in ongoing discussions trying to come to a suitable agreement, with the IRD releasing a statement last month pledging that it will share any proceeds from the new antimalarial treatment with the local authorities of French Guiana.

A more recent international case occurred over teff grass (Eragrostis tef), an annual grass native to Ethiopia. In 2003, a Dutch company called Ancientgrain gained two patents for the processing and preparation of teff grain. The Netherlands patent system requires much less examination regarding patent applications and as such the company gained the ‘registration patents’ meaning they legally owned the rights to the use of teff grain. Over the last decade, as teff has increasingly become considered a super food in Western countries, Ancientgrain has been actively suing companies for commercially producing teff grain products due to patent infringements. One such case occurred in 2014 with another Dutch company called Bakels Seniour, which sold teff bread flour on their online sales platform. Ancientgrain obtained ‘prejudgment attached’, in which they secured compensation before the trial even began. Although this case is legally complex, it is a clear example of biopiracy in the agricultural sector, with a native Ethiopian biological resource being used for the monopolisation of the global teff market by a company based in another continent.

To combat this, many researchers are collecting genes and publishing them in scientific domains (such as Genbank and seed banks). Sharing genetic sequences as open data is an attempt to prevent large firms and organisations from claiming novelty and/or uniqueness, two criteria for being awarded a patent.

Patents were initially developed to protect novel inventions and to promote innovation and development. However, many anti-biopiracy activists, as well as some academic and scientific communities are calling for a universal change in the patenting system.

If you would like to read further on the subjects covered in this article, please see the links below:

Related News & Blogs

‘Sowing the seeds’ for food security in Uganda: CABI supports training for Quality Declared Seed production

CABI has been working with Zirobwe Agali-Awamu Agribusiness Training Association (ZAABTA), the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF), the National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO), and Integrated Seed Sector Developmen…

21 May 2025